Row Spacing

The Importance of Row Spacing

The manipulation of row spacing is a conceptually simple management tactic that can have a sizable impact on weeds in some crops. Row spacing (along with seeding rate) determines the crop arrangement in a field, altering how fast the crop canopy closes (leaves from adjoining rows begin overlapping) and the ways in which weeds grow between crop rows. Weeds compete with crops for essential resources (sunlight, nutrients, water, and space); if they outcompete the crop this can lead to significant yield loss. Narrow row spacing reduces the time the crop needs to close the canopy, thereby providing rapid shading and decreasing weeds’ competitive abilities and simultaneously decreasing the reliance on herbicides later in the season.

What is the Critical Period for Weed Control (CPWC)?

Row spacing and faster canopy closure are important factors for the Critical Period for Weed Control (CPWC). CPWC is the period of time that a crop must be kept weed-free to prevent yield loss. Crops that rapidly develop a dense canopy often have a shorter CPWC. Crops are typically most susceptible to weed competition during their early growth stages. Each crop has a different CPWC which depends on the intrinsic biology of the crop (or even the variety) and environmental factors.

Highly competitive weeds that grow rapidly during this period can cause significant yield reduction even at low densities; wide-row spacing exacerbates the problem. For instance, soybean row spacing as wide as 36 inches is common for some parts of the US. With wider rows there is less shading of the ground and weeds densities are often higher; lack of crop shading allows weeds to grow taller and for relatively longer periods of time. Wide rows require additional weed control to compensate for reduced crop competition.

Studies have shown that weeds must be managed early and during the CPWC to protect crop yield and decrease the number of seeds the weeds produce at maturity. Weed seed production can replenish the soil seedbank with new seeds, which can be a problem in the following years.

Narrow Row Spacing

Reducing row spacing is an effective way to increase the competitiveness of some crops. Though there are exceptions, narrow row spacing generally leads to faster canopy closure, thus increasing weed suppression. Early crop canopy formation blocks sunlight, decreases weed seedling emergence, and suppresses the growth of emerged weed seedlings. The CPWC can be shortened with narrow rows, which may reduce the reliance on herbicides and/or improve overall weed control.

Narrow rows for soybeans have been classified to be 15 inches (or less). Narrow-rows for annual cereals are typically planted at 7 inches or less.

A long-term study in wheat has demonstrated that narrowing row spacing from 6 or 9 inches to 4 inches increased wheat’s competitiveness against goosegrass and gardencress. In narrow rows, both weed species produced less than five seeds per plant 60 days after wheat emergence (versus over 900 seeds per weed plant in wide row treatments). In addition, wheat yield was considerably greater in the narrower row treatments (Fahad 2015).

Crop Species is Crucial

A key consideration in choosing the spacing of crop rows is the nature of the crop species. Although research has revealed that narrow row spacing is beneficial for some crops, each crop varies in growth characteristics and CPWC. These physiological/CPWC differences, along with agronomic practices, dictate the ideal row spacing for each crop. While narrow row spacing can reduce CPWC, it can sometimes reduce yield if plants are spaced too closely together due to competition between the crop plants themselves. There is also evidence that narrow rows may promote disease incidence in susceptible crops. It is therefore important to know the limits of each crop, and space accordingly both between and within rows.

Narrow row corn and cotton have not shown to have a consistent benefit for weed control. While narrow row corn has increased yield in some studies, its effect on weed competition is less clear. Studies with cotton have shown some benefits for increased competition with weeds; however, production in narrow rows has led to an increase in trash (leaf and stem tissue) in harvested fibers.

In-Depth Look: Soybean

Soybean row spacings of 30- to 36- inches are common in some regions of the country due to prevailing equipment setups and production practices, but planting in narrow rows can improve weed control. Soybean is the grain crop that consistently benefits from narrow row spacing. Its upright growth habit and numerous branches make it well adapted to narrow row spacing, particularly that of 7.5 inch rows. Studies dating back to 1966 demonstrated row spacing of 10 inches reached 95% sunlight interception 17 days earlier than 30 inch rows; full canopy closure happened 40 days earlier in narrow rows (Shibles and Weber 1966).

One of the most troublesome weeds in the eastern US is Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) a pigweed species. Palmer amaranth is a highly competitive broadleaf weed, able to grow much faster than most soybean cultivars in warm regions. Worse still, a single plant can produce hundreds of thousands of seeds, thus increasing the size of the soil seedbank in a single season.

Research indicates that 7.5-inch row spacing greatly affects Palmer amaranth, in particular, due to early canopy closure which blocks photosynthetic active radiation. In 7.5-inch soybean rows, it was found that Palmer amaranth emergence was decreased by 76% compared to fields with no soybean; while common cocklebur emergence was reduced by 33% (Jha 2017). Other species of pigweeds, common lambsquarters , and other weeds that are often found in soybean fields in the United States are similarly affected by soybean shading.

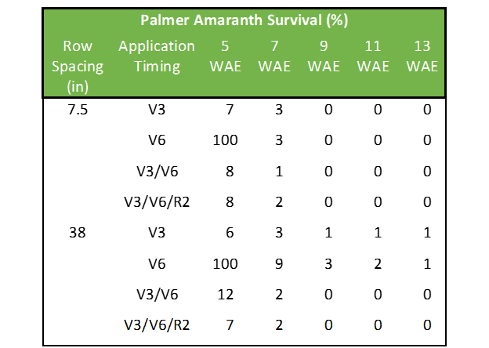

Utilizing a drill seeder to plant in narrow rows may lead to an increase in seeding rate. The competitiveness and vigor of soybean planted at these higher rates, along with narrow rows, can help manage weeds that emerge both early and late. In some cases, multiple postemergence herbicide treatments are not needed due to the weed suppression caused by soybean competition. A study testing Palmer amaranth and their survivability when sprayed at different time intervals within 7.5- and 38-inch rows reported the narrower (7.5-inch) rows saw less palmer amaranth survival regardless of the timing of herbicide treatment (Jha 2008).

Reducing herbicide usage not only saves money but also reduces selection pressure for herbicide-resistant biotypes. Herbicide-resistant (HR) weeds are becoming an increasingly severe threat to farms across the country. Palmer amaranth is among the most damaging HR weeds, and is well known for growing far taller than soybean. They have become resistant to multiple soybean herbicides such as glyphosate (RoundupTM) and chlorimuron (Classic). Narrower row spacings reduce the emphasis on herbicides which in turn reduces selection pressure for herbicide-resistant biotypes.

Pigweed is only one example of the suppressive effect of soybean on late emergence weeds when planted in narrow rows. Many other weeds, such as barnyardgrass, common cocklebur, common ragweed, and lambsquarters are all affected in comparable ways.

Common Concerns:

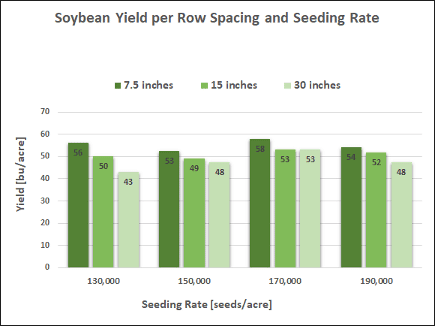

Profitability: While many new planting and field management strategies appear beneficial overall, the question of profitability will always be of concern. It is important to recognize that the impact of narrow row spacing is influenced by region/climate. Hence, profitability will likewise vary. A study conducted in Michigan tested four soybean seeding rates along with three-row spacings (7.5, 15, and 30-inch rows) and demonstrated the economic viability of planting in rows as narrow as 7.5-inches. Profits increased by an average of 14% with 7.5- and 15-inch row spacings compared to 30-inch rows (Harder 2007).

Another study conducted in NY found either 7.5- or 15-inch row spacing had higher yields and increased profits compared to 30-inch rows (Cox et al. 2011). This particular study saw greater yields in 7.5-inch rows than 15-inch. Although the standard row width of 30-inches is common due to prevailing equipment setups, planting in narrow rows can improve weed control and compensate for the initial cost.

Disease Severity: Disease is another troublesome variable that can adversely affect soybean fields. While narrow rows can improve weed management, some diseases are favored by narrow rows because the soybean foliage and soil surface remains wet for longer periods of time.

For example, bacterial diseases as well as frogeye leaf spot or white mold may be of particular concern. These are examples of soybean diseases favored by extended periods of leaf or soil surface wetness. This disease may become prominent if the field has had a history of having these pathogens in it. If diseases that are favored by longer periods of leaf moisture are a concern, consider planting resistant cultivars.

In Conclusion

Narrow row soybean is considerably more competitive against many weed species due to earlier canopy closure than in wide row soybean. Although there have been concerns surrounding this practice in the past, an understanding of row spacing and soybean growth patterns can play a significant role in integrated weed management.

References:

- Bagavathiannan, M.V., Norsworthy, J.K., Smith, K.L., Neve, P. (2011) Growth and reproduction of barnyardgrass (Echinochloa crus-galli) under different soybean densities and distances from soybean rows. In: Proceedings of the Southern Weed Science Society Meeting, San Juan, PR.

- Bradley, K.W. (2006) A review of the effects of row spacing on weed management in corn and soybean. Crop Management 5(1). doi.org/10.1094/CM-2006-0227-02-RV

- Cox, W.J., Cherney, J.H. (2011) Growth and yield responses of soybean to row spacing and seeding rate. Agronomy Journal 103:123-128. doi.org/10.2134/agronj2010.0316

- Borger, C.P.D. , Riethmuller, G., D’Antuono, M. (2016) Eleven years of integrated weed management: Long‐term impacts of row spacing and harvest weed seed destruction on Lolium rigidum control. Weed Research 56:359-366.doi/full/10.1111/wre.12220

- Fahad, S., Hussain, S., Chauhan, B.S., Saud, S., Wu C., Hassan, S., Huang, J. (2015) Weed growth and crop yield loss in wheat as influenced by row spacing and weed emergence times. Crop Protection 71:101–108. doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2015.02.005

- Harder, D.B., Sprague, C.L., Renner, K.A. (2007) Effect of soybean row width and population on weeds, crop yield, and economic return. Weed Technology 21:744–752. doi.org/10.1614/WT-06-122.1

- Jha, P., Kumar, V., Godara, R., Chauhanc, B., (2017) Weed management using crop competition in the United States: A review. Crop Protection 95:31-37. doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.06.021

- Jha, P., Norsworthy, J.K., Riley, M.B., Bridges Jr., W. (2008) Influence of glyphosate timing and row width on Palmer amaranth (Amaranthus palmeri) and pusley (Richardia spp) demographics in glyphosate-resistant soybean. Weed Science 56:408-415. doi.org/10.1614/WS-07-174.1

- Lambert, D.M., Lowenberg-DeBoer, J. (2003) Economic analysis of row spacing for corn and soybean. Agronomy Journal 95:564-573. doi.org/10.2134/agronj2003.5640

- Shibles, R.M., Weber, C.R. (1966) Interception of solar radiation and dry matter production by various soybean planting patterns. Crop Science. 6:55-59. doi/abs/10.2135/cropsci1966.0011183X000600010017x

- Thompson, N.M., Larson, J.A., Lambert, D.M., Roberts, R.K., Mengistu, A., Bellaloui, N. and Walker, E.R. (2015) Mid‐South soybean yield and net return as affected by plant population and row spacing. Agronomy Journal 107:979-989. doi:10.2134/agronj14.0453

- Tursun, N., Datta, A., Budak, S., Kantarci, Z., and Knezevic, S. Z. (2016) Row spacing impacts the critical period for weed control in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Phytoparasitica 44:139–149. doi.org/10.1007/s12600-015-0494-x

Authors

- William Sargent

Contributors

- Lovreet Shergill

- Kurt Volmer

- Victoria Ackroyd

- Claudio Rubione

- Mark VanGessel